Russian Gold and Silver Articles of the 12th—17th centuries

One of the halls of the Armoury in the Moscow Kremlin has on display a collection of articles made by Russian gold- and silversmiths of the 12th—17th centuries, the artistic and historic value of which can be hardly overestimated. It comprises all sorts of royal and church utensils: gold and silver bowls, loving cups, chalices, crosses, gospels and icons in magnificent covers. This artistic heritage, represents a wide variety of forms, original designs, and complicated techniques, which speak of high standards of craftsmanship of the masters.

Most of the objects made of gold, silver, pearls and gems were therefore intended for the elite: the royal family, princes and high clergy. In spite of the the masters who created all those valuables strove to preserve in their works the elements of traditional folk art. This desire of theirs showed itself in the shapes and ways of decorating the objects. Russian jewellers practised various techniques of working precious metals: casting, chasing, repousse, carving, incision, niello, filigree, painted enamel, and made a good use of gems.

There are relatively few monuments that represent the 12th—15th century Russian jewellers’ art. Among them we can find objects made by gold- and silversmiths of Kiev, Vladimir, Suzdal, Novgorod, Ryazan. Peculiar techniques, compositions and ornamental motifs were typical of their art.

A wonderful example of the Ryazan masters’ skill can be given by the articles of the so-called “ryazan treasure”. It was found in 1822 on the territory of the town Staraya (Old) Ryazan destroyed by Tatars in 1237. The treasure is a woman’s decoration for ceremonial wear which consisted of several pieces of different purpose but the same style. Among them there are massive round “kolty”—pendants attached to a headdress, “barmy”—yoke-necklaces, bracelets, rings and ear-rings. The shapes of objects, combination techniques, the colour of the enamels prove that they were made by the 12th century Ryazan craftsmen.

The unity of style shows itself in all the pieces not only in their shape but also ornamentation. Holy images stand out in bright colourful spots against the glittering gold surface of the “kolty” and “barmy”. The smooth metal surface intensifies the enamel portraits, whereas the pearls and a broad edging in filigree stresses their finesse and subtlety. Numerous unfaceted gems in high casts raised above the filigree design add splendour to the “barmy”. Despite the complexity of the filigree ornament and opulence of precious stones, the components of the Ryazan treasure retain the unity of style, colour, shape and pattern.

The progress of art in Ancient Russian principalities was interrupted by the Tatar-Mongolian invasion. The centres of Russian culture were destroyed. After the terrible devastation the country’s cultural life resumed at a very slow pace.

The city of Moscow played a great role in the development of Russian gold- and silversmithery in the 15th century. Moscow craftsmen fostered on the rich heritage of local art schools were in those days in the vanguard of architecture, painting and jewelry-making.

Moscow silversmiths were most successful in mastering the art of filigree. Its main motifs—a continuous twining stalk or spaced out bunches of herbs covered the metal surface like fine lace. The cover of the hand-written Gospels contributed by the Metropolitan Simon to the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Moscow Kremlin in 1499 is a proving example of the Moscow silversmiths’ brilliant skills.

The front of the Gospels is covered in dense metal lace. However, the density of the ornament does not conceal but further intensifies the airiness and lightness of the filigree. Its fine design frames in a most delicate way “The Crucifixion with Interceding Saints” situated in the centre of the cover against the emerald-green enamel background. The master’s rich fantasy, subtle sense of rhythm and motion, his steady skill mark the emergence of a new trend in Moscow applied art.

Beginning with the 16th century the unification of principalities around Moscow started, and the development of Russian artistic culture went along one line, while the local trends were gradually levelled up. The new style was pompous, festive, colourful.

The development of gold- and silversmithery in Moscow was promoted by the opening of artistic workshops at the Grand Prince’s court—the Armoury, Pastel, Silver Chambers and others. Gifted craftsmen from all over the country moved to the capital. While keeping the old artistic traditions, the Moscow jewellers mastered a large number of new techniques in the production and decoration of valuables.

Those days saw the flourish of the niello technique. The gold dish presented by Ivan the Terrible to his wife Maria Temryukovna in 1561 is one of the best monuments of niello art. The centre of the dish is taken up by a large flower in repousse. Its somewhat spiral petals cover almost all the surface of the dish. Only round the brim there is a narrow black-velvety design of beautifully intertwined flower stalks. Due to the precision of ornamentation, the deep colour of niello and virtuosity of make the dish is considered to be a masterpiece of Russian decorative and applied art.

Another magnificent example of niello work is the gold censer made to the order of the Tsarina Irina in 1598. As for its shape, it is a miniature one-dome temple- A floral nielloed pattern of herbs, sprouts and flowers covers the upper part of the censer. On its sides there are nielloed images of the Apostles. Their fugures are a little elongated, which makes the lower part of the temple lighter and gives it a vertical sweep. Round gems adorning the censer make it still more sumptuous.

The gold mounting of the icon Hodegitria made in 1560 is remarkable for its exceptionally fine filigree ornament, beautiful design and subtle colours of the enamel. In the sixteenth century filigree was no longer independently used for decorative purposes. We find it in combination with varicoloured cloi- sonn6 filling the open spaces of the filigree in the shapes of flowers, leaves and buds. The effect of such festive ornament and the play of colours was indeed charming.

The cover of the Gospels contributed by Ivan the Terrible to the Cathedral of the Annunciation of the Moscow Kremlin in 1571 is an object of exceptional beauty, skill of performance and delicate colours of cloisonne. The lace of filigree patterns spotted with enamels takes up all the surface of the cover. The combination of filigree and cloisonne gives the pattern a three-dimensional effect. The play of light on the gems standing out in relief adds expression to the cover.

The sixteenth century is considered by right the golden age of Russian decorative and applied arts. The articles made by the Moscow jewellers of that time speak of an unprecedented scope of their creative imagination and skill.

A considerable amount of space in the Armoury is taken up by the collection of gold and silver tableware made in the Kremlin workshops in the 16th—17th centuries. Ancient Russian gold and silver tableware has a pronounced traditional character. Boat-shaped dippers, bowls, “charkas” (small cups for wine), “bratinas” (loving cups) were adorned with repousse, niello, engraving and sometimes coloured enamels. Various sorts of stones were also used for making tableware—jasper, onyx, sard, rock crystal.

The seventeenth century saw the flourish of the Moscow Kremlin workshops, which became an original school of artistic craftsmanship. Gavrila Evdokimov, Yuri Frobos, Vassili Terentiev, Vassili Andreyev and other gifted masters worked in the Kremlin.

Among numerous exhibits dating back to the 17th century the articles decorated with enamels attract greatest attention. They are particularly bright, colourful, sumptuous. The gold chalice contributed by the Boyard Morozova to the Chudov Monastery in 1664 can be considered a masterpiece of enamel art. Everything about it is permeated with a poetic sense of beauty: pure lines of design, joyful combinations of colours, emeralds, rubies, sapphires used in order to enliven the composition.

The same traits showed themselves in the gold bowl shaped like an opening flower which was presented by the Patriarch Nicon to the Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in 1653. The master who worked at the enamel decoration deeply felt the beauty of his country and strove to convey it through his creation. The enamel of extremely bright and deep colour rivals with the brilliant colour of gems—pure and transparent. The gems are set in gold casts with white enamel which makes them similar to wild flowers.

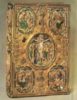

The massive cover of the Gospels was made in 1678 by a group of craftsmen of the Gold Chamber. They developed great skills in mastering transparent and opaque enamels. Their combination resulted in an extraordinary play of light.

The 17th century jewellers were equally successful in the niello technique. The heritage left by engravers and niello-masters is really great. The 17th century niello technique differed considerably from that of the previous century—dense hatching was used along the lines of the pattern making them thicker. In the late 17th century engraved images came into use, their plots being borrowed from book illustrations and engravings.

The silversmiths of such towns as Yaroslavl, Nizhni Novgorod, Kostroma and others also made great progress in the seventeenth century. The forms and decor of the objects they produced have a distinct local flavour. They are more heavily decorated, brighter in colour and closer to folk art.

But it was the town of Solvychegodsk that made the greatest contribution into the development of Russian decorative and applied arts of the 17th century. It holds a place of its own in the evolution of enamel art. In the last quarter of the 17th century—earlier than in Moscow—a perfectly new technique of painted enamel came into being there. The Solvychegodsk enamels which were called “ussolye” had distinct features of the new time’s art. The “ussolye” enamels combined floral patterns with the images of birds, animals, landscapes and even human beings. This type of d6cor reflected man’s new attitude to art and reality.

The rich collection of gold and silver articles in the Armoury traces the evolution of the jeweller’s art—one of the oldest types of arts and crafts. It gives a good idea about artistic culture, high skills of the masters and the people’s creative talent in those times.