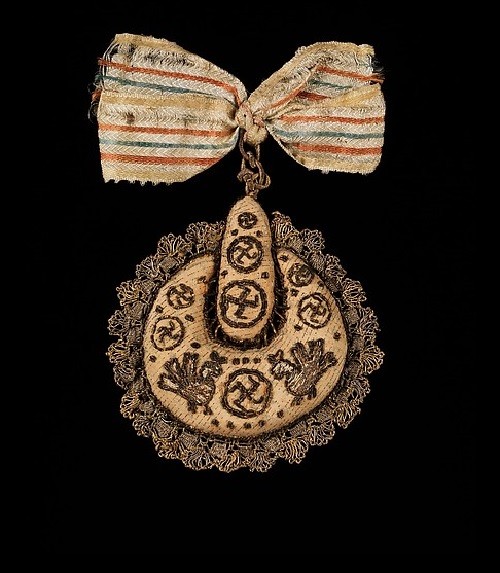

Swastika ancient symbol of good luck in Russia. On the territory of Russia, the swastika is known from Paleolithic times. The swastika was used in ceremonies and construction, homespun production: in embroidery on clothing, carpets. Household utensils were decorated with a swastika. It was present in icons. In 19th-century Russia the swastika was a heraldic symbol along with the imperial eagle. In Slavic cultures the shape is a manifestation of the sun, worshiped for its majesty and life-giving qualities. Braid ornaments were a common part of the maiden’s festival costume in Russia (picture above). The swastika is an ancient symbol of good luck in Russian culture. The combination of this with the flanking birds creates appropriate symbolism for a wedding.

From the collection of Natalia de Shabelsky (1841-1905). Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the Caucasus, the swastika can be seen on the rocks of Ingush towers, religious buildings and cemeteries, located in the perimeter of tower complexes built between X and XVII centuries AD. Such complexes are located mainly in Dzheyrahsky district of Ingushetia, in small quantities are also found in the Sunzha district of Ingushetia. Swastika as a three-beam solar sign, one of the national symbols of the Ingush and placed on the flag and coat of arms of Ingushetia.

Also swastika can be seen in some of the historical monuments in Chechnya, in particular, on the ancient tombs in the Itum-Kale district of Chechnya (the so-called “City of the Dead”). In pre-Islamic period the swastika was a symbol of the god of sun Dela-Malchus.

Swastika was displayed on some banknotes of the Provisional Government in 1917 and some printed with clichés “kerenki” Soviet notes that had circulated from 1918 to 1922.

Swastika and censorship in the Soviet Union

In the early years of the revolution swastika gained a certain popularity among artists who sought new characters for a new era, but its end put article “Warning”, published in the newspaper “Izvestia” in November 1922, by the People’s Commissar of Education A.V. Lunacharsky:

“In many decorations and posters mistakenly used incessantly ornament, called a swastika. Since the swastika is a deeply counter-revolutionary cockade of German organization “Orgesh”, and recently acquires the character of a symbolic sign of all fascist reactionary movement, then I warn you that the artists in any case should not use this ornament for producing, it has deeply negative experience especially on foreigners”.

In 1926 was published the first part of the fundamental ethnographic research on Russian folk costume of Meshchora, by Boris Kuftin (1892-1953). Edition contained a rich illustrative material, including swastica ornaments. After 1933, all such studies have been discontinued, no more publication has appeared. Distributed to libraries books, for the most part, have been destroyed, and the remaining central libraries upgraded to a closed-end fund in special storage (Spetskhran).

Swastika can be found on almost all items of Russian folk art – ornaments in embroidery and weaving, in carving and painting on wood, on the spinning wheels, Val, and gingerbread boards on Russian weapons, ceramics, Orthodox religion, on towels, valances, aprons, tablecloths, belts, men’s and women’s shirts, kokoshniks, chests, casings, jewelry, etc.